| |

CHURCHES OF

THE GOLDEN VALLEY

|

|

Nearly forty years

ago Nikolaus Pevsner wrote: “There

are not many counties in England of which

it can be said that, wherever one goes,

there will not be a mile which is

visually unrewarding or painful.”

Traffic in Hereford itself is horrendous

nowadays, and things may have changed

marginally elsewhere in the county, but

the Golden Valley, the valley of the

River Dore, still reflects all that he

and many others have written, extolling

the delights of this most secret place.

The Dore rises not far from Hay-on-Wye

and joins the Monnow at Pontrilas, near

the mediaeval fortress of Ewyas Harold,

built by William FitzOsbern in the late

11th century. |

With its associated stream,

the Escley Brook, it flows south-east parallel to

the upper reaches of the Monnow itself, its

gently wooded hillsides dominated by the towering

outline of the Black Mountains to the west.It is

a magical valley, its name possibly deriving from

the Welsh “dwr”, meaning

“water”, or possibly the French monks

of Dore Abbey’s mistranslation of

“d’or”, French for

“gold”.

The churches of the area are justly celebrated.

All of them are open and welcoming to visitors

and obviously greatly loved by parishioners. They

have one unifying element: most of them are of

Norman origin, reflecting the power of the Barons

who protected England from the marauding Welsh.

Three in particular, can be attributed to the

same builders: Kilpeck, Moccas and Peterchurch.

The first two are small three cell buildings of

nave, chancel and apse, whilst Peterchurch is on

a larger scale with a fourth cell suggesting

there was once a central tower. All have details

in common, either a moulded string course round

the apse or flat vertical buttresses. Rowlstone,

with its square east end, is linked also to

Kilpeck by virtue of its sculptured south

doorway, but the jewel of the valley is what

remains of the great Abbey of Dore. No county,

wrote John Betjeman, has a church as wonderful as

Abbey Dore, whilst Simon Jenkins describes it as

“a corner of France dropped into an English

meadow….a most sublime spot.” Yet to my

mind it is quintessentially English.

*****

ABBEY DORE,

St. Mary (formerly DORE ABBEY)

|

|

Dore Abbey was

founded by twelve monks from Morimond,

the least known of the five great

Cistercian houses in France, in 1147.

Morimond had daughter houses in many

parts of Europe, though Dore was the only

one in England. Perhaps Robert, Earl of

Ewyas, met the Abbot of Morimond on the

Second Crusade, and offered him land in

Herefordshire.

What remains today are the crossing,

transepts and chancel of the monastic

church, together with a seventeenth

century tower, all built of red

sandstone. The nave was pulled down at

the Dissolution in 1537, together with

all the conventional buildings, and the

remainder fell into gradual disrepair,

until it was restored by Viscount

Scudamore in the 17th century. |

Scudamore obtained the

services of John Abel to design new roofs, the

screen which separates the transepts from the

chancel and other furnishings, as well as the

glass which adorns the east window. The minstrels

gallery was placed against the west wall in the

first decade of the 18th century. Further periods

of neglect followed, and the furnishings were

once again repaired and re-ordered, this time by

a local architect, Roland Paul, beginning in

1901, and it is noticeable that much love and

pride is bestowed on the great church today.

The great feature

of Dore Abbey is the sumptuous Early

English chancel and the eastern piers,

each with fourteen shafts, the triple

lancet widows, and the double ambulatory,

each of its four pillars having eight

shafts. This composition has been

mentioned in the same breath as the east

end of Wells Cathedral by more than one

writer, and no praise could be higher.

Only the profusion of architectural

fragments which litter the floor of the

ambulatory are an eyesore, though not so

the magnificent bosses, rescued from the

nave roof, which can be examined at close

quarters: the Coronation of the Virgin,

Christ in Majesty, a monk kneeling before

St Catherine, and another kneeling before

the Virgin. Many retain traces of colour.

I first came here nearly half a century

ago, but Dore Abbey is a church to be

visited again and again; the rewards just

get greater and greater..

|

|

|

*****

BACTON, St. Faith

|

|

A small church

close by Abbeydore, with nave and chancel

in one. Notable for the alabaster effigy

of Blanche Perry, a maid-in-waiting to

Queen Elizabeth I, before whom she

kneels. The long inscription ends thus:

SO THAT MY THYME I THUS DYD PASSE AWAYE

A MAEDE IN COURTE AND NEVER NO MANS WYFFE

SWORNE OF QUENE ELLSBETHS HEDD CHAMBER

ALLWAYS

WYTHE MAEDEN QUENE A MAEDE DYD ENDE MY

LYFFE |

*****

BREDWARDINE, St. Andrew

|

|

The nave is early

Norman, with herring-bone masonry on the

lower part of the north wall, originally

with doorways north and south. The former

is blocked, but the latter remains,

complete with an enormous lintel, carved

with rosettes. It also shares a heavily

rolled moulding with the south door at

Rowlstone. The chancel was rebuilt in the

14th century at an angle to the nave, and

contains two large tombs. On the north

side, the damaged effigy of a knight,

possibly Walter Baskerville, who died in

1369, and on the south a finely carved

alabaster effigy, thought to be Sir Roger

Vaughan, who succeeded Baskerville to the

Lordship of the Manor, and was killed at

Agincourt in 1415. The tower was added in

1790, on the north side of the church,

possibly replacing a Norman central

tower. |

Bredwardine

stands close to the River Wye, at the foot of a

steep hill, and is a renowned beauty spot. The

diarist Francis Kilvert was Rector from 1877

until his death two years later.

*****

CLODOCK, St. Clydawg

|

|

Christianity came

to Clodock early in the 6th century, when

Clydawg, son of the King of Ewyas, was

murdered during a hunting

expedition. He was buried

near the riverbank, and a column of fire

was seen to rise from the grave,

prompting the local Bishop to order an

oratory to be built on the site.

The walls of the present church date from

Norman times, and the living became the

responsibility of Llanthony Priory, a

short distance across the Black

Mountains. The internal

furnishings date almost entirely from the

reforms of Archbishop Laud, retaining the

original altar and three sided rails,

three decker pulpit with tester and

a complete set of box

pews. There is a large west

gallery of about 1700, complete with the

original music desk. Like St.

Margaret’s, Clocock remained under

the jurisdiction of St. David’s

until transferred to the Diocese of

Hereford in 1858. |

In the

churchyard there are nearly 900 gravestones,

mainly from the 18th and 19th centuries, all in

their original positions. By all

accounts some 1600 burials were recorded in the

parish between 1813 and 1850. Where

did they all come from?

*****

KILPECK, St. Mary & St. David

|

|

Even if it were

not adorned by some of the best and most

original sculpture in England, Kilpeck

would still be marked down as one of the

finest and most complete Norman village

churches, and of all the churches in

Herefordshire it receives the most

visitors. It is built of red sandstone

and consists of nave, chancel and apse,

with just a bell-cote added later. The

exterior is punctuated by flat

buttresses, and a corbel table runs all

round.

But it is the carving that makes Kilpeck

famous, for it represents the finest

remaining work of the so-called

Herefordshire school of carvers, whose

work began at Shobdon in 1140 and moved

to Kilpeck in about 1145. |

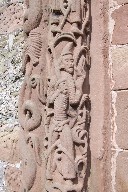

Far removed from the

mainstream of Norman sculpture, the carvings show

the influence of the Vikings, Saxons, Celts,

Franks and Spaniards, and display a vigour and

originality not found elsewhere. On the corbel

table we find sacred motifs (the Lamb and Cross),

animals (notably a lovable dog and rabbit),

wrestlers, a female exhibitionist (a

Sheila-na-gig) and many other comic-strip

figures. The south door is sumptuously decorated.

The tympanum shows a Tree of Life, whilst the

outer order of the arch is decorated with linked

medalions containing dragons and birds.

The shafts consist of thick

snake-like bodies, with two long wiry figures,

whose pointed caps and tight clothes have the

parallel folds like ribs that are characteristic

of the School. There is decoration on the west

front, too. The window has shafts of beaded bands

of interlace, and three magnificent dragons heads

protrude from the wall. Many of these motifs

recur at other Herefordshire churches, and

occasionally in neighbouring Shropshire and

Worcestershire, though not elsewhere.

| The interior is

equally exciting. The apse is

rib-vaulted, and the ribs are decorated

with zig-zag, as is the chancel arch, but

each vertical pillar of the arch has

three carved figures, one above the

other, including St. Peter and St. Paul,

a most unusual feature, again suggestive

of the innovative local school of

carvers. Pevsner, in fact, makes an

interesting suggestion that the church

may have been begun in about 1135 and

that ten years later the Shobdon workshop

moved in to decorate Kilpeck when their

work there was done. |

|

|

*****

MADLEY, Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary

|

|

An unusually large

and beautiful church. The rare dedication

refers to the statue of the Virgin which

was housed in the crypt during the Middle

Ages, making Madley a centre of

pilgrimage. This crypt, with its central

pillar, has recently been restored.

The present church dates from three

distinct periods of building. Of the

original Norman cruciform church only the

north transept remains as what is now the

north porch. About 1220 it was largely

pulled down to make way for a new nave

with aisles, chancel and tower, whilst a

hundred years later the chancel was again

rebuilt in the French style, with a

sumptuous polygonal apse. The crypt was

also built at this time, and shortly

afterwards the Chilston Chapel, in effect

an outer south aisle, was added. |

The most memorable features

of the church all date from this last rebuilding.

The east window has reticulated tracery whilst

its two companions have the latest geometric

tracery. There is a profusion of ball-flower

decoration both inside and out: on the sedilla

and in a frieze immediately below the eaves. It

also appears on the elegant windows of the

Chilston Chapel. The east window contains some

beautiful stained glass, the most notable being

three panels from an early 14th century tree of

Jesse, including perfectly preserved panels

depicting Ezekiel and King Josias. The choir

stalls, complete with simple misericords also

date from the 14th century, whilst the huge

Norman font (c.f. Bredwardine and Kilpeck) is

said to be one of the largest in England.

*****

MOCCAS, St. Michael

|

|

|

|

Take away the

bellcote and two 13th century windows and

Moccas remains the perfect Norman village

church: nave, chancel and apse. Not that

any village remains nearby today, for the

church is situated alone in the grounds

of Moccas Court, built in 1775 close to

the River Wye, to designs by Robert Adam.

The first church at Moccas was founded by

the Welsh Saint, St. Dubriciuth, and

rebuilt on high ground in the second

quarter of the 12th century to designs

familiar from Kilpeck and Peterchurch,

though in fact Moccas may have come

first. The apse has the moulded string

course below the window line similar to

the other two, but no pilasters. The nave

has two Norman doorways with badly eroded

tympana. |

That on the south has a

tree of life flanked by human figures and animals

(c.f. Kilpeck). The north windows contain two

complete and beautiful stained glass canopies of

the 14th century, and in the centre stands an

early 14th century tomb-chest surmounted by the

effigy of a cross-legged Knight, which has been

badly re-tooled.

*****

PETERCHURCH, St. Peter

|

|

|

|

At first glance

the most distinctive feature of St.

Peter’s is the tall broach spire,

made of fibreglass and lowered on to the

tower by helicopter in 1972. It is

gleaming white and visible from miles

around. Hopefully it will mellow with

age. The main body of the church is an

unusually large and important Norman

structure consisting of four parts: a

nave, an apse and, apparently, two

chancels. As one of these is square, it

presumably supported a central tower at

one time. Pevsner describes the sequence

of arches as memorable, two surmounted by

saltire crosses and one decorated with

zig-zag. The roof of the apse is painted

blue with golden stars, another memorable

effect. Externally the apse is similar to

Kilpeck, with a roll moulding below the

windows and flat pilasters. The view

would be greatly improved if some of the

trees and shrubs close to the apse were

removed. |

*****

ROWLESTONE, St. Peter

|

|

On high ground

between the River Monnow and Dulas Brook,

St. Peter’s was originally a simple

Norman building of about 1130, of a nave

and chancel, although it has been

suggested that there may have been an

apse (c.f. Kilpeck, Moccas). The present

east wall was reconstructed in the 15th

century, when the large north window was

also inserted into the nave, and the

tower with its pyramid roof added in the

16th century.

The importance of Rowlestone lies in its

carved decoration, executed by the same

sculptors who worked at Shobdon and

Kilpeck. The Christ in Majesty in the

tympanum above the south doorway is

surely one of the master’s finest

works, almost identical with the lost

Majesty at Shobdon. |

The figure is in a halo,

with the knees wide apart and the feet together,

and the skirt having the tense, stringy folds

characteristic of the Herefordshire School. The

four supporting angels fly upside down, making a

highly accomplished composition. The heavy roll

moulding above the door is supported on capitals

decorated with birds and a Green Man.

The chancel arch is equally impressive. The same

birds are there (an obsession with the

Herefordshire carvers) and figures of winged

angels and haloed figures. Those on the south are

set upside down. Could this have been

carelessness, as Pevsner suggests, or a reference

to the legend that St. Peter was crucified upside

down? Above both capitals the abaci are carved

with further bird motifs, echoed once again in

the two 14th century iron candle brackets in the

chancel. Rowlestone Church deserves to be much

better known; many of those who visit Kilpeck,

not five miles away, have never heard of it.

*****

ST. MARGARET’S, St. Margaret

|

|

The thrill of St.

Margaret’s is best summed up in the

words of John Betjeman. “My own

memory of the perfect

Herefordshire,” he wrote in 1958,

“is a spring day in the foothills of

the Black Mountains and finding among

winding hilltop lanes the remote little

church of St. Margaret’s, where

there was no sound but a farm dog’s

distant barking. Opening the church door

I saw across the whole width of the

little chancel a screen and loft all

delicately carved and textured pale grey

with time.” Set in a large churchyard

which in summer resembles a wild flower

meadow alive with grasshoppers and

butterflies, St. Margaret’s consists

of a nave and chancel with an oversized

weatherboarded turret.

|

It is basically Norman with

later additions, but everything pales into

insignificance before the screen, described by

Pevsner as one of the wonders of Herefordshire.

It is really a loft resting on two carved posts,

their delicate, lacy ornament surrounding two

little niches near the top. The delicate carved

foliage on the front of the loft is in well nigh

perfect condition, and the coving has ribs

meeting at right angles, with tiny carved bosses

at each junction. The screen is similar to

several in Wales, including that at Patrishow,

not far away across the Black Mountains, and

similarly remote. Until 1852, St.

Margaret’s, together with other churches in

the Hundred of Eywas, was in the Diocese of St.

David’s. It has recently been

sympathetically re-roofed, and despite its

remoteness it is always open and holds regular

services as well as an annual Flower Festival.

St. Margaret’s is one of the few places

which are as thrilling to visit for the twentieth

time as for the first, although it certainly

doesn’t get any easier to find! Its peace

and serenity remain as potent today as they did

fifty years ago.

*****

TURNASTONE, S. Mary Magdelene

|

|

A small mediaeval

church standing less than half a mile

from Vowchurch, on the road to

Michaelchurch Escley. The nave and

chancel are all in one, crowned by a

handsome ceiled wagon roof with bosses.

The south doorway is late Norman,

decorated with very rustic carved

capitals. At the west end is an

attractive little weatherboarded. bell

turret with a pyramid roof.

| There are

two monuments of note: an incised

slab of 1522 to Thomas Aparri and

his wife, their portraits

embellished by a little satyr in

a big hat playing a pipe, and a

copiously decorated tablet with

figurines to Mrs Tranter, of

1685. |

|

|

|

*****

VOWCHURCH, St. Bartholomew.

|

|

The nave and

chancel, which are continuous, like its

neighbour at Turnastone, were consecrated

in 1348, but incorporate the remains of

an earlier building. At the west end is a

timber bell turret, dated 1522.

The interior is a shock. To support a new

roof timber posts were set against the

stone walls to support the tie beams,

queen-posts and collar beams. It looks as

if a barn was built inside the original

walls in 1613, and at the same time the

carpenters added the chancel screen, the

only division between nave and chancel.

All this woodwork is stained black, and

claims that John Abel (1577-1674) was

responsible for this work are surely

misplaced, for it cannot begin to compare

with his work at Abbeydore and various

market halls throughout the county. |

Tom Muckley, July 2007

tommuckley.co.uk

|

|